Tag: point reyes national seashore

Eight days ago, on December 14, 2021, Point Reyes National Seashore’s Superintendent, Craig Kenkel, announced...

A female merlin perches on a fence post at Point Reyes National Seashore.

As I mentioned in my last post...

Coyote Standing in New, Green Grass

I was out at Point Reyes yesterday. It was a fairly good day wildlife...

Where did that gopher go?

This badger was digging at both ends of a gopher tunnel. While he was digging...

I saw this coyote at Point Reyes yesterday. He or she has a nice new winter coat. I also saw and photographed...

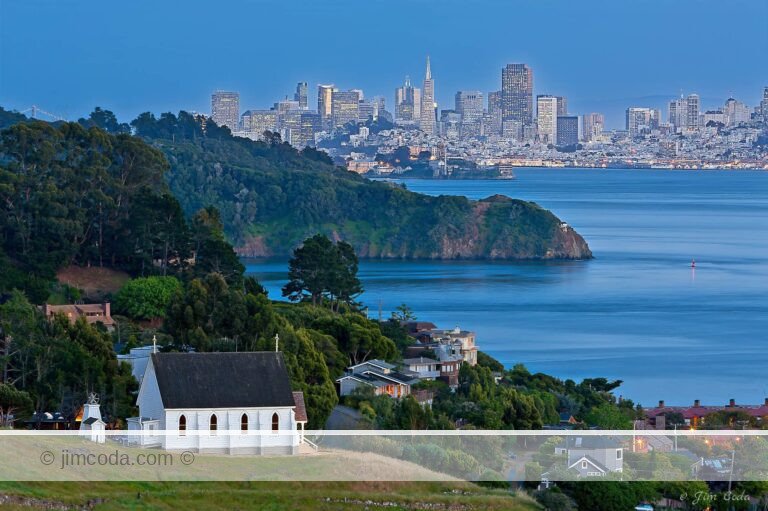

I was looking for a photo I took about 10 years ago and stumbled upon this one. I don't think I ever...

Coyote in the Ranching Area of Point Reyes National Seashore.

This coyote is standing in a ranch pasture...

Bull Elk Lying in an Early-Growth Silage Field

Some ranchers who lease ranch lands from the National...

Easy-Going Cat

Here’s a bobcat I photographed in the late afternoon. He was very patient with...

A Bobcat Daydreams

Here’s a bobcat I saw a few days ago at Point Reyes. The sun was shining in...

Blacktail deer clears a fence at Point Reyes.

The most common way barbed-wire fences kill deer and elk...

No articles found

Prints for sale

Browse my selection of photos for sale as fine art prints

Filter by category

Sorry, no prints in this category