Tag: Olare Motorogi Conservancy

I’ve noticed that in my photos where a cheetah is walking, its ears are often pinned back. I...

These two lion cubs were play-fighting in the Olare Motorogi Conservancy just outside the north boundary...

A cheetah mother starts to hunt in the Olare Motorogi Conservancy. She has three hungry cubs to fee...

Here is a lion that I saw every day while shooting in the Olare Motorogi Conservancy in Kenya. He co-leads...

A lion cub practices its fighting skills with an impatient adult. Cubs need to learn to survive and...

I love observing and photographing cheetah cubs at play. This cub was very entertaining.

One of the...

I photographed this cheetah cub in Kenya’s Olare Motorogi Conservancy just north of the Maasai...

This is one of two male lions that were the leaders of a pride that I saw every one of the four days...

I photographed this male lion at sunrise in the Olare Motorogi Conservancy. I just read that they weigh...

When I arrived at Gamewatchers Safaris’ Porini Lion Camp, the first cat I expected to see was,...

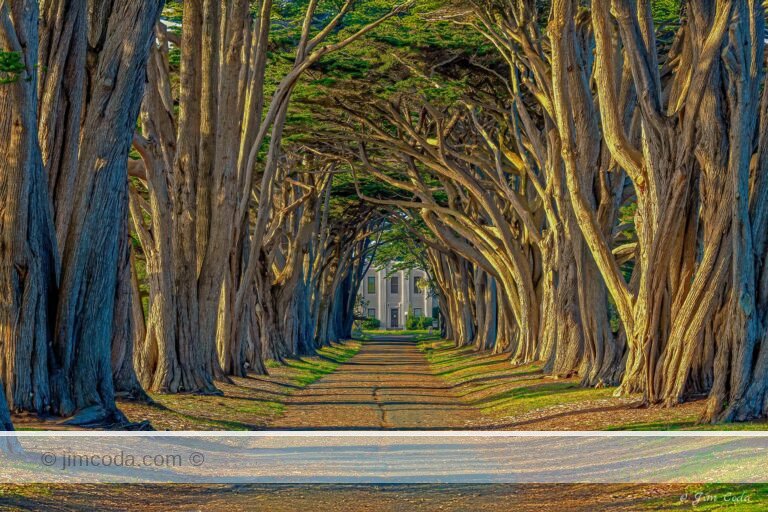

This golden light is why we nature photographers try to be out there before the sun rises. When I was...

To finish the story I started a week or so ago, after those great four days with Gamewatchers Safaris...

No articles found

Load More Articles

Loading...

Prints for sale

Browse my selection of photos for sale as fine art prints

Filter by category

Sorry, no prints in this category